Anzac memorial and graves in Turkey. Photo by Hayden Spurdle.

Service & sacrifice

I had the privilege of speaking about Anzac Day at church services either side of the 100th anniversary of the landings at Gallipoli. In between those I attended the dawn parade and service at Pukeahu, the most moving one I’ve attended.

Anzac has an important place in our national identity and it also has gospel resonance. It is always a complex task to extract lessons from history because we view events with the benefit of hindsight and with a cultural perspective that is very different from our forebears.

However Anzac is still profoundly significant as we seek to raise up and encourage a new generation of leaders in New Zealand.

I suggest we can learn these lessons from those young men who marched off with enthusiasm and, in many cases, were killed or returned marred by the horror of their experiences.

The importance of sacrifice

One of the most cited verses at Anzac services is, “Greater love has no one than this: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.” It comes from John 15:11-17 where Jesus is talking to his mates about love, sacrifice, calling and obedience.

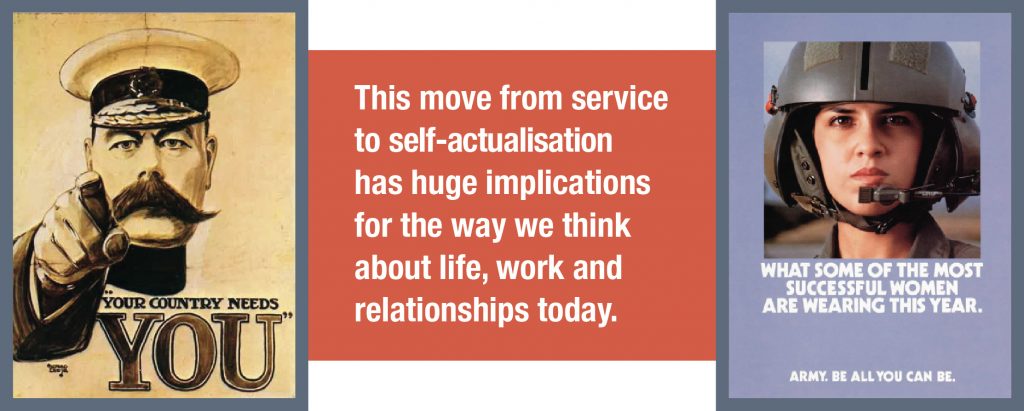

A famous recruiting poster for the British army in World War I had the pointing Lord Kitchener with the words “Your Country Needs You” boldly emblazoned below. The last recruiting poster I saw for the British Army had the tag line “You need the Army.” This move from service to self-actualisation has huge implications for the way we think about life, work and relationships today.

Jesus is looking forward to his own death and is laying down a marker for the disciples. Discipleship is all about living as Jesus lived, in relationship with him. One of the things this lost generation reminds us of is the cost of service. Of the 100,444 troops and nurses who served overseas in World War I, 18,697 were killed and 41,317 wounded. This 58% casualty rate is in the context of a NZ population around 1 million.

The Otago Settlers Museum has two exhibits that helped me understand the loss. They have a Dunedin street map from WWI with a cross on each household where someone died, a different colour for each year of the war. They also have a couple of photographs tracking what happened to local groups of soldiers. A photo of The Port Chalmers Boys has marked on it who was killed and who was wounded. Virtually no one got through unscathed.

Martin Luther King, Jr said, “If a man hasn’t discovered something that he will die for, he isn’t fit to live.” I would amend this to say “someone who he will die for.” We have been reminded by brothers and sisters in Nigeria, Kenya, North Africa and other places that people are dying for Jesus today.

Howard Guinness, who helped found what became TSCF during the 1930s, wrote a booklet called Sacrifice that inspired a generation – quoted in part below. I believe it describes some current students and recent graduates of TSCF. I think we are seeing a quiet resurgence in biblical discipleship and a new generation of leaders contending for the gospel on campus, in the workplace and in the world.

The difficulty of understanding the times

In the first week after war was declared in New Zealand, 14,000 volunteered. The enthusiasm for adventure, fuelled by patriotism, was encouraged in many churches and Christian publications. As people began to understand destruction and death in the trenches, they had to re-evaluate the old idea that it was a brave and noble thing to die for one’s country.

Of those who did not share the enthusiasm for war were 2,500 New Zealanders who objected to military conscription on the grounds of conscience. Some served in noncombatant roles. Others refused to have anything to do with what they regarded as an immoral war; 250 were imprisoned and 14 were transported to Europe and forced to endure field punishment in an attempt to break their spirits.

Many who objected did so from Christian convictions but their stand was rarely supported by the church of the day.

Where was God in this spectrum of engagement? How did being a child of the British Empire shape and inform a world view? How do we decide our response to the big issues of our day?

Some of the things people passionately believe at one point in time may be seen as untrue with the benefit of hindsight. We need to beware of an accommodating faith that gives a disbelieving world less and less to disbelieve in, and seek wisdom to engage with faith and compassion on issues of justice and equality.

We need more prophets and poets who can help us see beyond the near horizon. We need leaders who, like the men of Issachar, “understood the times and knew what to do.” Proper biblical engagement is at the heart of this process and we need help from the global community of God’s people to see beyond our own cultural blind spots and ideologies.

At this year’s Summit, it was encouraging to see students and graduates from NZ and the South Pacific interacting with John Stackhouse. He helped us think beyond piety and contemporary Christian mythology to what authentic faith looks like as we serve God’s purposes in the world.

The reality of the presence of God

Inside the National War Memorial Carillion, an inscription in blue and gold from Psalm 139 sits high up at the front.

Where can I go from your Spirit? Where can I flee from your presence?

If I go up to the heavens, you are there; if I make my bed in the depths, you are there. If I rise on the wings of the dawn, if I settle on the far side of the sea, even there your hand will guide me, your right hand will hold me fast.

If I say, “Surely the darkness will hide me and the light become night around me,” even the darkness will not be dark to you; the night will shine like the day, for darkness is as light to you.

It is an awesome reminder that no matter what, no matter where, God will shield, comfort, protect, illuminate and ultimately overcome. As we continue to take the Good News to the world, Jesus is with us. Service goes beyond seeking God’s help in the midst of chaos. It is also being aligned with God’s purposes. God is sovereign and we serve one who knows what he is doing and what he has called us to participate in as he builds his Kingdom.

For all the rhetoric, those who died in World War I did not achieve a legacy of peace and freedom. As many of the Great War memorials were being consecrated, clouds of a new war were already darkening the horizon. Numerous wars, conflicts, genocides and terrorism have followed.

The Cenotaph War Memorial near Parliament has a series of plaques, each with a single word – “Valour,” “Honour” and ideas less frequently found on war memorials such as “Security,” “Wisdom,” “Justice,” “Peace,” “Purity” and “Sacrifice.” They represent aspects of the character of God. Some of the iconography is drawn straight from the Christian story; “Peace” has a dove with an olive branch in its beak and “Sacrifice” a cross with a crown of thorns.

When Te Papa erected a cross in the entrance hall for the World War I centenary, it received complaints such as: “I find it deeply offensive to see a cross used in this way, many atheists and people of other faiths died in the Great War.” When I mentioned this in a talk on Anzac, someone said to me afterwards, “But it was only because Christianity was the dominant faith that they used the cross.”

True, but why did the cross become the symbol of the Christian faith? It is quite unusual for a method of criminal execution to become a religious symbol. But the cross is the place where Jesus accomplished his mission and defeated sin and death. Ultimately, it is not a symbol of death but of life and hope. All those cemeteries of white crosses point to the hope of resurrection.

At the heart of service and sacrifice is an unshakeable conviction that the only hope for peace and reconciliation in the world is Jesus. Being and sharing this Shalom is where wholeness, health, peace and integrity connect.

There were clues of this through our remembrances of Anzac. This year there was a light show on the old Dominion Museum Building, which now houses the Peter Jackson Great War exhibition. At the end of the light show three projections had Maori and English words. “Rangimarie – Peace,” “Aroha – Grace,” and “Tūmanako – Hope.” It would be hard to think of three words that better encapsulate the presence of God and the central message of the Good News.

Next year TSCF will celebrate 80 years of sharing the good news in the campuses of Aotearoa New Zealand. At our recent board retreat we were encouraged to hear some who had studied in the 1960s and 1970s share what TSCF has meant to them.

As current students also shared, a common theme emerged. It was transformation. Involvement with TSCF as students had a lasting effect, encouraged biblical thinking, whole life discipleship and early steps in leadership.

I am profoundly grateful for where we have come from but I am even more interested in where we are going. Ultimately, Anzac is not just about our history and our identity but about our future. Who will follow in the footsteps of that generation forging a future for NZ, the Pacific, and the world?

We work to grow people of influence who will participate in what God is doing through history for eternity – leaders who will serve and sacrifice, who will battle as loyal soldiers and will be men and women of peace.

Where are the young men and women of this generation who will be faithful even unto death?

Where are those who will live dangerously, and be reckless in his service?

Where are the men who say “no” to self, who take up Christ’s cross to bear it after him, who are willing to be nailed to it in college or office, home or mission field?

Where are the men and women who have seen the King in his beauty, by whom all else is counted but refuse that they may win Christ?

Where are the adventurers, the explorers, the buccaneers for God who count one human soul of far greater value than the rise or fall of an empire?

Where are the men who glory in God-sent loneliness, difficulties, persecutions, misunderstandings, discipline, sacrifice, death?

Where are the men and women of prayer?

Where are the men and women who, like the Psalmist of old, count God’s word of more importance to them than their daily food?

– Howard Guinness